New Chanel Sunglasses 2014

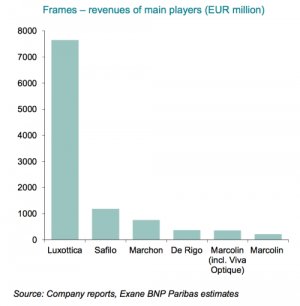

Luxottica, the dominant frame producer, owns a portfolio of eyewear brands that includes Persol and Ray-Ban, the latter of which is the biggest brand in the market. It holds the licenses to produce eyewear for global fashion brands such as Chanel, Armani, Prada and and manages the distribution of its products through 200, 000 wholesale doors. In 2014, the Italian company generated over €7.6 billion (about $8.5 billion) in revenue. In addition, Luxottica owns the Sunglass Hut retail brand and is a retail company in its own right, with over 7, 000 stores worldwide, giving it a majority share of the eyewear market.

Luxottica, the dominant frame producer, owns a portfolio of eyewear brands that includes Persol and Ray-Ban, the latter of which is the biggest brand in the market. It holds the licenses to produce eyewear for global fashion brands such as Chanel, Armani, Prada and and manages the distribution of its products through 200, 000 wholesale doors. In 2014, the Italian company generated over €7.6 billion (about $8.5 billion) in revenue. In addition, Luxottica owns the Sunglass Hut retail brand and is a retail company in its own right, with over 7, 000 stores worldwide, giving it a majority share of the eyewear market.

The second biggest player, the Safilo Group, holds licenses for Dior, Fendi, Céline and . It employs more than 150 designers, adding more than 3, 000 new models to the market a year, sold through a network of 90, 000 wholesale doors. The company reported €1.17 billion (about $1.33 billion) in revenue in 2014 and annual growth of about five percent.

Marchon Eyewear, De Rigo and Marcolin, the three smaller players in the market, each have licensing deals with major global brands. Marchon holds licenses from, Valentino, Salvatore Ferragamo and Chloé; De Rigo holds Lanvin, and ; and Marcolin holds, Balenciaga, Tod’s and Ermenegildo Zegna.

A New Number Five?

In September, Kering told press, “The current size of the Kering brands’ business is roughly €350 million [making] Kering one of the top five players in this industry… Kering will fully control the eyewear value chain, from design to product development and supply chain, and from branding and marketing to sales.”

But why did Kering choose to go it alone? In the statement announcing the launch of its eyewear division, Kering highlighted that, "The premium segment of the eyewear business is currently growing in the high double-digits."

The importance of eyewear as an entry-level product for its brands speaks to the other key advantage stemming from Kering’s move: control. The Exane BNP Paribas report states, “The ubiquitous distribution typical of most license contracts adds to brand trivialisation risk.” By taking its eyewear in-house, controlling development, distribution and sales, Kering could “maintain desirability through perceived exclusivity.”